Your Computer

In this section, we'll learn a little bit about how our computer works using a tool called the command line.

Do you really know your computer?#

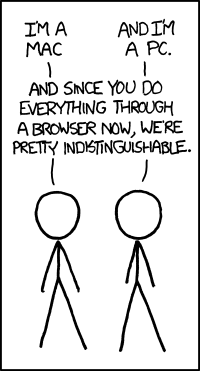

For many of us, computers are a means to an end, a tool for a job. We use our computers to write papers, send email, talk to our friends and family, watch Netflix, or maybe play a game. Maybe you use your computer to make art, do science, or analyze statistics. Most likely, you have a preference for a PC or a Mac, even if the only reason you can articulate is the way it looks.

But how well do you really know your computer? Do you know what operating system it runs? Which version of that operating system? When was the last time you updated it? Have you ever upgraded your hardware? Do you even know which pieces of your computer are the hardware? As an exercise, see if you can find the name and version of your operating system. What other information can you find out?

For a device as ubiquitous as the computer, most of us don't know a lot about how they work. On the one hand, that's great! Why should you have to learn the intricacies of bits, bytes, circuits, and microprocessors to do something basic like write an email? On the other hand, what if you want to use the power of your computer to count words, make a map, or analyze a network? When it comes to working with data, having a deeper understanding of what your computer can do can be to your advantage. Not everything can be done in the browser. After all, computers started their life as counting machines. If you want to work with large sets of data in an efficient manner, ask a computer to do what it is best at: count things, find patterns, or carry out a series of operations. That is not to say computers can do all the work! Humans have their own part to play. Someone has to give the instructions, write the programs, make connections, or see the larger context of the computer's work. In this section, we'll learn about one specific way to give instructions to your computer: the command line.

Command Line#

Most of us interact with our computers or phones through highly visual interfaces. We know what button to press because of the stylized image representing it. We understand what it means when a website has a blue "f" or when a friend sends a thumbs-up emoji. Your computer, regardless of operating system, wants to interact with you via visual cues. We call these Graphical User Interfaces aka GUI (pronounced gooey).

But there's another way. You can interact with your computer entirely via text commands through something called a Command Line Interface or CLI. When you see a hacker typing green text into a black box in a movie, they're using the command line. But the command line isn't just for hacking. Not only can you perform a number of different actions on your computer, many pieces of software can only be used through the command line. You can use the command line to create, move, or copy files. You can convert images or find and replace. You can run complex programming languages, or just write a simple script to automate a repetitive task. There are many tools for working with data that require you to use the command line.

Just like HTML and CSS, you do not have to memorize every command. There are plenty of sites to remind you of the commands or that provide existing scripts to help with a task.

How it works#

For Mac users:

- Search and open (

Command + Space) for an app called Terminal. A white box should appear. - You should see some information about you computer, then your name, then a dollar sign. It could look like this

38371-Lib-Brooks:~ mackenzie$. - Typing in this program is a little different than typing in a document. You cannot use your mouse to click into text and change what is written. Pretend you're working at an old school computer where there is no mouse. If you want to change what you've written, use the arrow keys or backspace to navigate.

- Type in the letters

pwd. No spaces, no capitalization. Hit enter. This command stands for "print working directory" and tell us where we are in the file structure. Confused yet? Scroll down to the next section for more context.

For Windows users:

- Search/open a program called

cmd.exeor Powershell.

If you're using a Chromebook, or another device, you may not be able to participate in the command line activities, since the nature of your device limits access to your computer.

Syntax#

Just as we learned the unique syntaxes for HTML and CSS, issuing commands in the command line requires a new syntax. Here's the basic format:

$ command parameters -flag

The $ is not something you type. It appears at the command prompt as a way to indicate that you should begin typing. Most tutorials you see will start their commands with the $ to show that this is the beginning of a command. Think of it like a period at the end of a sentence. It is there to visually prompt you.

The next part of the syntax is the command. Usually this is a single word or series of letters, like pwd ls or cd. Go ahead and type one of these commands into the command prompt, then press enter.

Next, we have parameters, or some kind of direction for our command. The command cd stands for "change directory." Often, we need to tell the command prompt where we want to change into, so we need to give it a parameter. The command cd Desktop would change our directory (more about directories in a moment) to the Desktop. So in this case, Desktop = parameter.

Finally, we have a flag, usually expressed as a dash + letter -f. Flags are options that you might turn on to change the nature of your command. Enter ls -l into the command prompt and press enter. ls stands for list directory contents, and in this case, the -l flag means list the contents in the long version. Now try just ls without the flag. Notice the difference?

File Structures#

Before we go any further, there is a key concept you must understand about how your computer stores information.

All of the stuff on your computer, the documents, music, PDFs, videos, is organized into folders (also known as directories). Modern operating systems, especially on a Mac, as well as cloud-based storage like Google Drive or Box, obscure this fact. But it's essential to understanding the command line, working with data, and publishing content to the web. When you are issuing a command, or referencing a file, in any type of coding context, that action is being done with an awareness of the file structure, even if you personally don't realize it.

For example, when you wanted to insert a photo of a cute kitten into your webpage, the only way to make it work was if the image of the kitten was in the same folder as your HTML document. When you wrote <img src="kittens.jpg"> you were giving the browser both the name of that file, as well as the path. If both the image and the HTML document were in the same folder, then the path was unnecessary. But say you created a folder for all your images, called "images," within the same folder as your HTML document. Now, your HTML might need to look like this <img src="/images/kittens.jpg">.

As humans, we rely on search functions frequently to deliver the files we're looking for. But code, as expressed through commands or HTML, doesn't have a built-in search function. And even if it did, it still might not know exactly which file you meant. You have to help the computer find its way to the file you are referring to.

If you recall from the previous section, websites are just made up of files and folders too. When you upload something to Web, it is being added to a folder on someone else's server. Have you ever looked at a URL up close? Some browsers, like Safari, will try to hide it from you. But if look closely, you should see the directory structure at work. In this URL, "faculty-and-staff" is a subdirectory of "english-department" https://my.wlu.edu/english-department/faculty-and-staff.

If you're looking real close, you might also notice that there are dashes in the folder/directory names. This is another important lesson! Browsers and computers have a hard time with spaces. It doesn't necessary behave the same way a character like a letter or a number does. Browsers will often replace a space with the characters %20. It's best practice to avoid using spaces in your file names. I know your computer lets you name things with spaces, but it will save you a lot of headaches if you avoid them. Use dashes, underscores, or something called camelCase where the second word is capitalized to set it apart.

Activities#

There are many existing tutorials for learning the command line. The activities in this section will rely on those tutorials so you get a sense of the different types of materials out there for learning a new technology skill. Feel free to seek out videos on YouTube, LinkedIn Learning, or Code Academy if that's your style.

Activity 2.1#

Work through The Command Line Crash Course. This tutorial accommodates both Windows and Mac people. This tutorial is about brute force repetition, so just lean into that method of learning for right now.

Activity 2.2#

The Programming Historian is a wonderful website offering tutorials (in multiple languages!) on digital research methods in the humanities. They have two tutorials on the command line that are slightly more advanced than Activity 2.1. Work through the relevant tutorial for your operating system.

Mac users: Intro to the Bash Command Line

Windows users: Intro to Powershell (This one gets pretty advanced, don't worry if you can't get all the way through.)

Activity 2.3#

In this activity, we'll apply our new command line skills to working with a corpus of textual data. While we're not quite ready to learn about text analysis, when we get there, we will need to have our data ready. You might notice I just threw some new words at you - "corpus" and "textual." Don't freak out, these are just specific words to refer a collection (corpus) of textual (not numbers) data. Instead of a spreadsheet with rows and columns, we'll be working with individual documents groups together into folders. I am purposely giving you a kind of messy, but very much real, dataset to explore. It's okay if you get confused, but try to use these new commands

- Download this zip file and save it to your Desktop.

- Unzip the file by double clicking or using an Extract All option. A zip file is a compression method for bundling up a lot of folders into one so it's easy to share.

- Open the command line shell, and navigate to the folder you just downloaded.

- Use

pwdcdandls(Mac) ordir(Windows) to navigate through the RTP-1980s folder. - Can you mirror these action using your mouse and the Finder/Windows Explorer window? What are the differences?

- In a new document, answer the following questions:

- What is the basic file structure of the data set as you have received it? What about the file names? * What are the patterns? Where (or when) do the patterns change?

- What is the granularity (of the text files? Does each file contain one page? Issue? Reel? Volume? Year?

- Use cat to read a file. Find the manual for cat. What else can you do with this command?

- What happens when you type

ls *.2.txt? - Can you figure out how to list all the file names in RTP-1980s and send them to a text file?

- Last step: type history and paste your command history into the text file.

Resources#

- ExplainShell. Paste in a command and receive a definition.

- Sourcecaster by Thomas Padilla and James Baker. This site has example scripts for performing common tasks with files.