Data

In this section, we'll dig deeper into the fundamentals of working with data by concentrating on data structures and methods for cleaning messy data.

What is data again?#

In the last section, we got as far as defining data as "a value assigned to a thing." While that remains true, let's dig a little deeper. If we put on our humanities hat, we start to see data little more complexly.

In her article, "Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display," Johanna Drucker posits the following about data:

"To overturn the assumptions that structure conventions acquired from other domains requires that we re-examine the intellectual foundations of digital humanities, putting techniques of graphical display on a foundation that is humanistic at its base. This requires first and foremost that we reconceive all data as capta. Differences in the etymological roots of the terms data and capta make the distinction between constructivist and realist approaches clear. Capta is “taken” actively while data is assumed to be a “given” able to be recorded and observed. From this distinction, a world of differences arises. Humanistic inquiry acknowledges the situated, partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production, the recognition that knowledge is constructed, taken, not simply given as a natural representation of pre-existing fact."

This is a long quote, but the concept of "capta" is a useful one. Even if we don't go around calling everything "capta" instead of "data," it is a helpful reminder that data is constructed, especially but not only in the humanities.

Every single piece of data represents a decision that someone made. The number of rows and columns, the labels, the format, the extent or granularity of the values and the things - these are all choices. They are choices you should consider when creating a data set from scratch or when you use someone else's data. In the rest of this section, we will dig into the details of putting together a data set.

Data structures#

Data can exist in many different forms. You might imagine a "spreadsheet" when thinking about data, but in truth, there are a number of other ways to express and structure your data.

Tabular data#

This is our common spreadsheet data structure. Data fits into a table, in which each row represents a thing. Each column is a different field or modifier of that thing. The values reside in each individual cell. In the following table, each row represents one pet.

| PetID | Name | Animal | Breed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pet1 | Huxley | Cat | Tabby |

| Pet2 | Harper | Dog | Flat Coat Retriever |

| Pet3 | Hobbes | Dog | Hound |

If you're new to making spreadsheets, it can be tempting to swap the rows and columns so that each column represents a thing. It can also be tempting to include empty cells as spaces or use visual cues like color or bold/italics to set apart text. These methods will certainly help you as a human, but it's important to keep in mind that most of the software that might process your data will not be able to understand these visual cues.

Most of the software that will process your data, whether it's for visualization or analysis, will want to see your data in a format known as CSV or Comma Separated Value. This format strips away any visual formatting and stores each cell in plain text, separated by a comma. So the above table about pets, would look like this:

PetID,Name,Animal,Breed,

Pet1,Huxley,Cat,Tabby,

Pet2,Harper,Dog,Flat Coat Retriever,

Pet3,Hobbes,Dog,Hound

The CSV format reduces file size, simplifies the content, and keeps the file from being dependent on proprietary software like Excel. Fortunately, you don't have to construct your data with commas. Applications like Excel or Google Sheets will let you save or export your file with the file extension .csv. It's a good habit to get into when working with data. You might also see .tsv for tab separated values, in which the spaces we see when we hit the tab button function as a single character.

Relational data#

For some projects, a single table quickly becomes insufficient. Perhaps your project requires collecting data about a group of people, the houses they live in, the land they occupy, etc. It might be time to look into using a database to store all that data. A database works on a relational model - you might have multiple tables, but they are connected through shared values or "keys." Using a database allows you to gather data about many different things, things that may require different fields to describe them. So my table of people may contain a column to note which house they live in, but I can rely on a totally separate table to list all the details about the house itself. This keeps me from cluttering my people table with information that isn't relevant to the main thing my row is about. Often, this is done with an ID number rather than the full title.

A second advantage of a database is the ability to ask questions of your data. To continue the example from above, I can now ask questions like: How many people live in houses that are yellow? Of the houses on this block, which ones are occupied by people with children? These questions require that I filter based on certain values within each distinct data table and combine them into a new set. Typically, questions like this are asked with a language called SQL or Structure Query Language (yes, another language with its own syntax!).

The basic syntax of SQL looks like this:

SELECT column_name,column_name

FROM table_name

WHERE column_name operator value;

Here's a more specific example. In this one, the asterisk means "give me everything." So I'm asking for all the fields that exist about the cats.

SELECT * FROM pets

WHERE animal='cat';

Asking these types of questions of data is often what humanities scholars are after when they decide to build a database. However, designing a database and the interface that goes along with it is a big endeavor, and often requires the help of a professional database designer. Databases can be built in many different types of software (you might encounter names like MySQL or PostgreSQL), but web-based databases will need to be installed on a server, not just your own computer. If you're undertaking a big project, it's important to assess your resources for creating a database. Fortunately, there are an increasing number of options for storing, visualizing, and analyzing data without database software. Creating well-structured data ensures that your data can be imported into and out of these tools with ease.

Data serialization#

Data serialization is the process by which data is transformed into another format that can be transferred or stored, then reconstituted. Often, this is necessary so that a programming language or software application can more easily and quickly do something with the data. With serialization comes a few different types of data structures that are important to know.

JSON, or JavaScript Objection Notation, is a way to structure data based on attribute-value pairs and curly brackets. Just like CSV, if you're working with a JSON file, it will have the file extension .json. You probably won't end up writing JSON from scratch, but you might have to convert your data to JSON for a certain application. And FYI, JSON is not only used with JavaScript.

Here's an example. Notice the level of structure introduced with the Address line. There are four fields and values (you might see this called an array) that modify one field, Address.

{

"PetID": "Pet1",

"Name": "Huxley",

"Animal": true,

"Breed": "Tabby",

"Address": {

"streetAddress": "555 5th St.",

"city": "The Couch",

"state": "Living Room",

"postalCode": "55555"

},

}

XML or Extensible Markup Language is more than just a serialized data format, it's also a markup language (like HTML). XML has been around a long time, so you will see it referenced in many Digital Humanities projects. XML is highly structured, but allows the user to define the tags that are used. A common application in humanities projects is the Text Encoding Initiative or TEI. TEI is used to markup humanities texts, just like you would markup a website, but instead you use tags like <l> for line and <epigraph> for epigraph. TEI allows you to do things like build a website for testing your ability to read rhyme and meter in poetry. It is a foundational practice in DH - the process by which a human interprets a text and encodes the meaning in a way that the computer can understand.

Example:

<lg rhyme="ABCCBBA">

<l>The sunlight on the <rhyme label="A">garden</rhyme>

</l>

<l>

<rhyme label="A">Harden</rhyme>s and grows <rhyme label="B">cold</rhyme>,</l>

<l>We cannot cage the <rhyme label="C">minute</rhyme>

</l>

<l>Wi<rhyme label="C">thin it</rhyme>s nets of <rhyme label="B">gold</rhyme>

</l>

<l>When all is <rhyme label="B">told</rhyme>

</l>

<l>We cannot beg for <rhyme label="A">pardon</rhyme>.</l>

</lg>

Textual data#

Not all data has needs to exist in a spreadsheet. In the humanities, we read a lot! We need a way to store textual data, such as a whole book, set of documents, or a century of newspaper articles. A later section will cover the ins and outs of text analysis, but if you're looking to analyze a corpus (another word for collection of texts) of some kind, you need to structure it in some way.

The common method for storing textual data is in a plain text format or with the file extension .txt. Plain text files are just that - documents without the formatting that comes from MS Word or other word processing applications. Just like our HTML documents or our CSV files, a text document simplifies the content for the computer. When we're counting the number of times Jane Austen used the word "honor" or looking for the use of the word "evolution" over time, we are concerned with the words in the text, not the way the text looks. Plain text format reduces file size to improve processing time and transfer of data. You'll probably want to use a text editor for viewing these files, just like we did when writing HTML.

Depending on what you're doing, you will also want to pay attention to the name and organization of your text files. If you noticed in the Voyant instance with Jane Austen, the title of each text was preceded by the year of publication. This file naming strategy makes it easy to sort the texts by their publication date. It's just something to pay attention to when constructing your corpus.

If you do care about what the text looks like, you might want to look for ways to analyze TEI documents, not just plain text. Text Encoding allows you to add details about the appearance of the text, perhaps there's another hand writing in the margins or use of italics or white space in poetry.

Data types#

Once you have settled on the right structure for your data, you need to consider the data types you will use in each field. Most programming languages accept the following:

| Data Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Strings or characters, often surrounded by quote marks | "String!" |

| Integer | 4 |

| Decimal | 4.10 |

| Boolean, another way to say true/false or yes/no | TRUE |

| Date, usually formatted as YYYY-MM-DD | 2019-10-20 |

| Time, usually formatted as HH:MM:SS | 10:17:26 |

There are a few others data types, but these will be most relevant in humanities projects. You will find that Excel loves to chew up and spit out dates unless you standardize formatting in this way.

Clean, tidy, and normal data#

As you start to work with data, you'll likely encounter these terms "clean, tidy, normal," used as adjectives and verbs. What do they all mean? How do you know when your data is clean and tidy? Maybe your data is just the black sheep of the family!

-

Cleaning data usually refers to the process of correcting the contents of your dataset. Typos, mistakes, new information can all be cleaned up after the data entry process is complete. You don't have to read every cell one by one, there are a number of tools and methods that will help automate this process. Often, visualization your data is a great way to find issues you didn't know you had.

-

Tidy data comes from the community around R, the programming language. Tidy data is well-structured, or as Hadley Wickham puts it, "Tidy datasets are easy to manipulate, model and visualise, and have a specific structure: each variable is a column, each observation is a row, and each type of observational unit is a table." Sounds familiar, right?

-

Normalized data is a database term. It refers to the process of structuring your tables to reduce redundancy and complexity. Normalized data should be easier for both humans and computers to understand.

Before we get to tools and methods for straightening up your data, let's take a moment for a pep talk. Data is messy! Whether you created it yourself or are using someone else's data, chances are, something will be wrong with it! The data entry process can be long, and it's easy to change your habits or come upon a better way to record things. This is normal.

To set yourself up for success, document your decisions as you make them. It is easy to absorbed in your work, make a decision, then put your work down and forget about the decision a week later. Keeping a log of changes will also help anyone else who might be contributing.

Be consistent! If you want to change a "T" to "True," it's easy to find and replace. It's not as easy to go through a mix of values.

Finally, remember what the computer is for. It can be tempting to embark on a cleanup project by hand, instead of looking for automated ways to correct your data. Knowing when to cleanup by hand or when to spend the time figuring out how to automate a task is a mark of experience. You won't get it right every time. But it is worthwhile to consider if something can be done in an automated way. Find and replace, when coupled with regular expressions, can be pretty powerful. It can feel like a waste to spend time automating a task when you could just do it, but the skills you learn in the process are valuable and can be applied on future tasks.

Data cleaning tools and methods#

Open Refine#

I try to avoid calling technology magic, but Open Refine is magic. It takes some getting used to, but it is indeed a "powerful tool for working with messy data." When you install and run Open Refine, it launches a local server on computer so you interact with the application in your browser. However, just because it's in your browser does not mean it's connected to the internet. Once you've loaded your data, you use the drop down arrows to access various tools for modifying your data. This is not a tool for scrolling through your data, it's used for targeted approaches to specific issues.

As an example, you can use the "cluster and edit" feature to find similar cells and standardize their contents. The "text facet" feature shows how many cells share the same value. When you sort by alphabetical order, it is really easy to see if you have entered the same name in two different ways.

There are a number of tutorials on the documentation page. Try this one, "Cleaning Data with OpenRefine" from the Programming Historian.

Excel#

Before you get to specialized tools like Open Refine, you can always use Excel or Google Sheets to check your work.

- Filter - use the filter feature to assess the contents of a single column. You can easily see if a cell is empty or has an incorrect entry.

- Data Validation - allows you to control what is entered into a cell. You can identify a list of options or select a specific data type.

- Formulas - there are plenty of spreadsheet formulas designed to work with strings of text. Use the help pages and a search engine to look for examples. There are multiple methods for splitting columns if you need to separate first and last names, or copy over the first half of a string.

Regular Expressions#

Regular expressions are a method for matching patterns in text. It's a set of special characters that when used together in certain contexts helps you find and replace in powerful ways. For example, you could find all the phone numbers in a text by looking for the pattern (###) ###-#### or all forms of "women" by using the pattern "wom.n" to replace the fourth character.

Regular expressions are awesome, but they can get frustrating quickly. Don't be overwhelmed by the complex patterns you encounter in tutorials. Even the basics can come in handy when cleaning data. Plus, there are a lot of resources out there for helping you use them effectively.

- Regular Expressions 101

- Beginning with Regular Expressions

- Cleaning OCR'd text with regular expressions

Data modeling#

Whether you are aware of it or not, data modeling is part of the data creation process. All of the decisions that you might make about your data, the format, the data types, the fields, help to form a model of your data.

Data modeling is a process that has been part of humanities work for a long time, just not by that name. When we attempt to organize the world through means like time periods, genres, or lists of names (prosopographies) or places (gazeteers), we are creating models that may or may not line up with reality. A model is an abstraction of an object. It can be a window into our disciplinary or personal values. The tools you choose to use will also contribute to the shape of your data model, as they can limit what and how you record your data.

There is a lot more to be said about data models and their role in humanities data work. There are different types of models and various ways to approach their creation and use. Data modeling has precise meanings within other disciplines, such as computer science. If you want to learn more, start with "Data Modeling in a Digital Humanities Context" by Julia Flanders and Fotis Jannidis.

But for now, let's return to that Miriam Posner article, "Humanities Data: A Necessary Contradiction."

"When you call something data, you imply that it exists in discrete, fungible units; that it is computationally tractable; that its meaningful qualities can be enumerated in a finite list; that someone else performing the same operations on the same data will come up with the same results. This is not how humanists think of the material they work with."

Data modeling is important precisely because it forces humanities scholars to clearly identify their goals and parameters. If you start a project without an initial idea of your data model, you could lose years sifting through archival material or transcribing handwritten notes. Or as Scott Weingart writes, "Humanistic data are almost by definition uncertain, open to interpretation, flexible, and not easily definable." To many humanities scholars, articulating a detailed data model can feel like a reduction of their subject. Or perhaps they're eager to dive into material, and then end up with a mess of a spreadsheet, unsure how to turn it into anything usable. It's okay if your data model grows and changes over time, but it should be recognized as a formal step in the process.

What does a data model look like? It depends on your project, but at its most basic, it could be a list of the fields in your spreadsheet, with a description of the values and their format. A data model for the Pets example above could be:

- PetID: a generic ID for each pet, max 6 alphanumeric characters

- Name: the given name of the pet.

- Animal: specify the type of animal from a controlled list: Dog, Cat, Bird, Gecko

- Breed: specify the breed of pet from a controlled vocabulary of Official Animal Breeds.

You might also want to indicate the extent of this list of pets. Who owns them? What the connection between them? Where did this information come from? Obviously, this is not an ambitious data project as it stands, but we can imagine some other categories to include: age, location, weight, health, favorite toy, favorite nap spot, etc. When I decide to add another field or change how I enter a value, I must update my data model to reflect these changes. Perhaps I realize halfway through my data collection that I should be using the scientific classification for animals, rather than a generic "dog" and "cat." If I had thought about my data model, I might have come to this decision at the beginning of my project. Think of data modeling as a favor to yourself and to anyone else who might encounter your data and wonder about your decisions.

Extending your data#

Once you have a good sense of how your data is going to look, it is worth considering options for extending your data. Do not assume you have to start from scratch. There are many other organizations and projects out there dedicated to creating data that can be used by others. Pelagios can help you describe historical places. PeriodO can help you describe time. Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus contains thousands of terms for describing art and material culture. And of course, libraries have long been in the business of organizing and sharing their data.

Linked data#

One way of extending your data is through the use of something called "linked data." Linked data is a method for structuring data so that it can be connected and linked to other data sets. You might also see this called the "Semantic Web." One way to create linked data is through the use of URIs or Uniform Resource Identifiers. The idea is that every thing in your data should be given a unique identifier. When you or anyone else references that thing, you use the identifier to indicate that we are talking about the same thing. The value of URIs becomes clear in any project with people. It's common for people to share the same names - giving them a unique ID number eliminates confusion and unites variant forms of the same name. But URIs are not just ID numbers, the should be HTTP URIs, meaning they look like a URL. Here's one for Audre Lorde: https://viaf.org/viaf/61565157/.

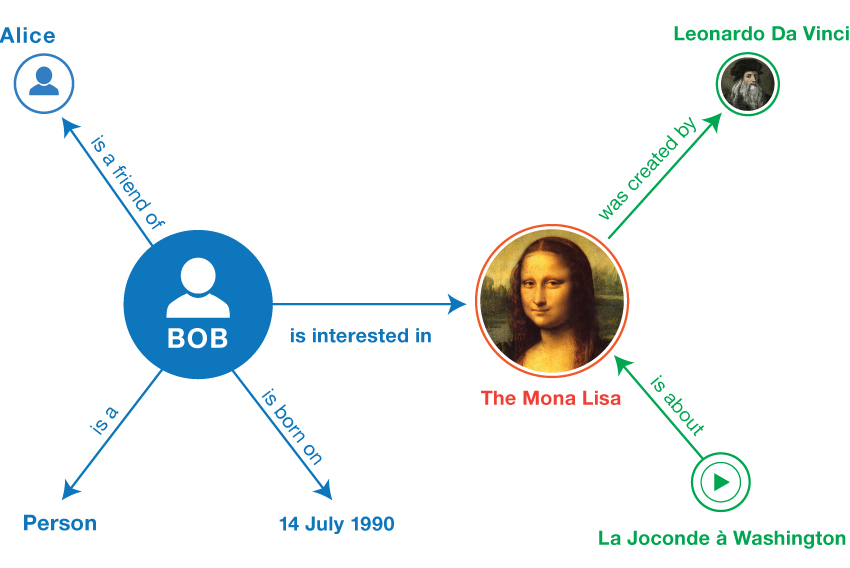

The other principle of linked data is the not only are the things given unique identifiers, so are the relationships between those things. We can standardize those connections and use URIs to express them. When we connect these URIs together, we start to see our data in a new way: the graph.

Source: RDF Primer

Source: RDF Primer

We haven't talked about RDF yet, but we can define it using terms we have just learned. RDF, or Resource Description Framework, is a data model for describing resources. It structures data through the use of triples or subject-predicate-object expressions, such as the ones we see in the image above. RDF can be serialized in several ways, through formats like Turtle, JSON-LD, RDFa, and RDF-XML. Okay, that was a lot of acronyms, but you should recognize some.

Here's some RDF about Audre Lorde:

<rdf:RDF>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://viaf.org/viaf/sourceID/DBC%7C87097946621565#skos:Concept">

<foaf:focus rdf:resource="http://viaf.org/viaf/61565157"/>

<skos:prefLabel>Lorde, Audre f. 1934</skos:prefLabel>

<skos:inScheme rdf:resource="http://viaf.org/authorityScheme/DBC"/>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#Concept"/>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://viaf.org/viaf/8101155708706522580005">

<rdfs:label>Sister outsider</rdfs:label>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://viaf.org/viaf/sourceID/NII%7CDA04877615#skos:Concept">

<foaf:focus rdf:resource="http://viaf.org/viaf/61565157"/>

<skos:altLabel>ロード, オードリ</skos:altLabel>

<skos:altLabel>Rollins, Audre Lorde</skos:altLabel>

<skos:altLabel>Lorde, Audre Geraldine</skos:altLabel>

<skos:altLabel>Lorde, Audre</skos:altLabel>

<skos:prefLabel>Lorde, Audre</skos:prefLabel>

<skos:inScheme rdf:resource="http://viaf.org/authorityScheme/NII"/>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#Concept"/>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

It's not that much fun to read, but you're a human, not a computer. In this example, you can pick out terms like "SKOS" and "FOAF." If you have been following along and nerding about about data modeling, go ahead and look those up or check out this tutorial: "Introduction to the Principles of Linked Open Data". If you're overwhelmed, tuck them in your pocket for later. This is a window into advanced work with humanities data. It's good to know it exists, but it's okay if you're not ready for it yet.

Activities#

Activity 3.1#

In this activity, we'll assess a dataset according to the criteria we've learned about in this section.

- Download the LexingtonCemetery.csv file.

- Open in Excel. Since this dataset is a CSV file, you may need to follow these instructions. The process may differ depending on what version of Excel you're using.

- Navigate to the Data tab in Excel.

- Select "From Text" then find your file.

- A wizard should pop up to walk you through the import process. It should automatically detect the commas, but if it doesn't, you will need to check the box to indicate that this file is delimited by commas. The data preview should separate each distinct column of data, rather than everything running together.

- What do you see? Take some time to explore this data by scrolling around. Get a sense of what is here and what might be missing. It might help to take a look at the cemetery website or to read this press release.

- In a separate document, start to draft a data model for this spreadsheet as you encounter it. Make note of the data types and formats, as well as suggestions for improvement. You'll turn in this data model with activity 3.3.

Activity 3.2#

Let's take Open Refine for a spin in order to clean up this data set.

- Download Open Refine and run the program. Follow the installation instruction if you get stuck. It should open a new tab in your browser with the address

http://127.0.0.1:3333/. This address is local to your computer, not something you can actually visit on the internet. - Import the LexingtonCemetery.csv file. You will see a page of import options, you should be able to accept the defaults.

- Spend some time clicking on all the options in Open Refine to see what happens. Set a timer and spend 10-15 minutes playing around with the software before you turn to documentation or instructions. What can you learn in this time? If things get too messy, you can always exit out and start over.

- Now answer these questions:

- What do the "Text Facet" or "Numeric Facet" features reveal about this data? Are there outliers that need investigation?

- Are there columns that should be split or joined? How would you do this in Open Refine (or Excel?)

- What columns would be best served by the "cluster and edit" feature? Why?

- Which columns need to be modified for consistency?

Activity 3.3#

Time to take a little step back from this data set and think about its potential. In the same document that you started in Activity 3.1, answer the following questions:

- What cleanup work does this data need to be more usable?

- Do you need to adjust your data model? How might you extend this data set?

- What research questions does it inspire?

- Do you need to conduct more research to learn about the people in this data set? How will you go about it?

- What (or who?) might be missing from this data set?

- We have yet to learn about the ins and outs of methods of analyzing data, but what would you want to do with this data?

- Update your data model to reflect your thorough thinking about this data set. It should include a list of each field, its data type, and any notes about the content of this field.

- Bonus: visit the cemetery! How does experiencing it in person change your view of the data? Does everything match up? Do you observe other things that should be in this data?

Activity 3.4#

Try your hand at creating your own dataset in a small group.

- Start with the Alumni Coeducation Correspondence, May 10, 1984 (report) from the W&L Digital Archive. Read over the report to get an understanding of what it is telling you. What is this report covering?

- Create your data model. Look over the consistent pieces of information included in the report. Choose what fields you think you should include. Why are you choosing those fields? What do you hope to use them to explore within the data?

- Take a few pages from the report and create your dataset. You'll be supplied with a Google spreadsheet to do this work.

-

After we come back from the small groups, compare your data model to that of other groups and answer the following questions.

- How are the models different?

- What did your group include that others didn't and visa versa?

- How do your fields change the questions you can ask the data?

- How could you use Open Refine to clean up the data you created?

Readings#

- Tidy Data for the Humanities by Matt Lincoln

- Big? Smart? Clean? Messy? Data in the Humanities by Christof Schöch

- Designing Databases for Historical Research

- Against Cleaning - W&L login required